Research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas.

The Case for a Fair Work Act, Part 3

Defining fair working conditions for all workers

Continuing our research series on fair work principles, we scratch the formidable surface of the huge topic of fair working conditions.

By Edwin Goh24 August 2021

In Part 1 of this research series, we called for updating employment categories and labour laws to reflect significant changes in power relationships between employers* and workers today. Basing our framework on the Fair Work Initiative, we proposed an overarching Fair Work Act covering five pillars of employment, namely fair pay, fair working conditions, fair contracts, fair management and fair representation.

*Note: The term ‘employer’ is used broadly throughout this piece, representing the party that either employs the worker or is the intermediary for the supply of jobs.

The previous instalment of this series, Part 2, focused on fair pay. We discussed how current minimum wage laws lack clear standards by which a ‘minimum’ should be set, leaving it prone to over-rely on stakeholder negotiation and under-deliver on notions of fairness. We argued that the minimum wage be defined as a level that allows workers to live adequately, i.e. a ‘living’ wage. We also proposed how the idea of fair pay and fair minimum wages could work for employment categories other than full-time employees.

This third instalment of the research series will focus on the next pillar of Fair Work, namely fair working conditions. What does fair working conditions mean in Malaysia? And how would it apply to different employment categories? We asked these questions and more in this article.

What do ‘fair working conditions’ cover?

The term ‘fair working conditions’ is broad and covers a range of areas including working age, working hours and break time, worker accommodation, leave days, workplace safety and more.

Historically, laws and regulations on working conditions were first introduced during the First Industrial Revolution to curb labour exploitation and impose standards for workers’ safety and health. Rapid industrialisation had drawn thousands of workers from agricultural farming to manufacturing jobs and the lack of regulations meant many were compelled to work long hours under extreme conditions, including children. To curb such abuses, the British government established the first landmark labour law known as the British Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802, at first to set the minimum working age and limit working hours. Since then, definitions and regulations for decent working conditions have broadened and evolved over the years.

There are a variety of definitions and scopes. For example, under the decent work pillar of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDG), a target related to working conditions is set out to “promote safe and secure working environments of all workers, including migrant workers, in particularly women migrants, and those in precarious employment”. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) also broadly defines working conditions as humane conditions of work necessary for peace and harmony of the society. A narrower definition is offered by the Oxford Internet Institute, which focuses mainly on workers’ health and safety at work and the risks emerging from the processes of work.

In view of the above, our scoping of ‘fair working conditions’ for the proposed Fair Work Act refers mainly to measures that mitigate direct on-the-job risks which include hours of work, occupational safety and health, leave days and worker accommodation. We also discuss how to treat a more debatable dimension which relates to measures concerning broader ‘off-the-job’ risks, such as against unemployment, skill relevance, illness and ageing.

What fair working conditions mean to workers will also vary greatly depending on their employment status. Different power relationships between employer and worker would necessitate different levels of interventions from employers and the government. In the following sections, we discuss the regulations and protections required for different employment categories to achieve the ideal of ‘fair working conditions’.

Current Malaysian laws on Working Conditions

After Independence, the Malaysian government built on the British Colonial Administration’s Labour Code 1933 to introduce the Employment Act 1955 for regulating the working conditions of employees. Over the years, the government implemented supplementary laws* and ratified 18 ILO conventions to shape working conditions that meet international standards.

*Note: Read Part 1 of our Fair Work Act research series to learn more about existing labour laws.

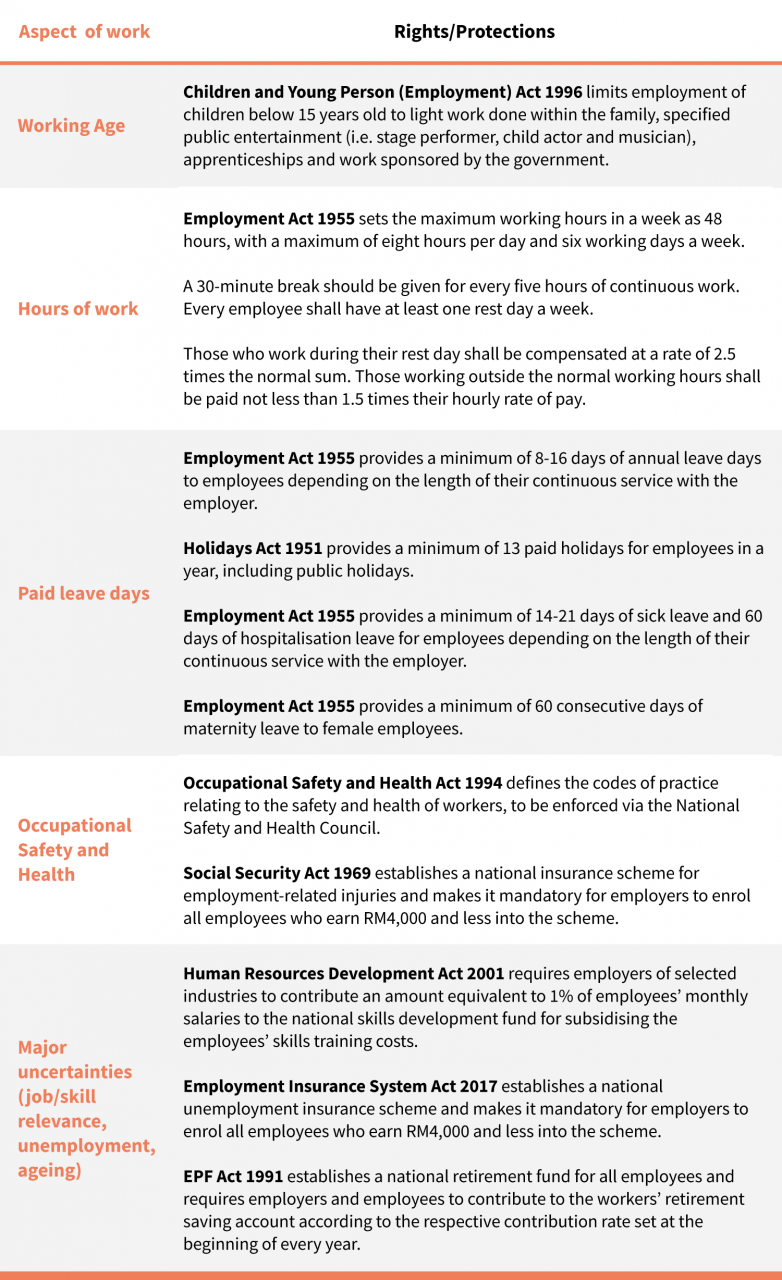

Key pieces of current legislation related directly to working conditions are outlined in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Current Malaysian legislation on working conditions

As mentioned in Part 1, the premise of most employment legislation today hinges very much on formal, full-time employees. There are few laws covering the working conditions of those engaging in relatively independent and flexible jobs such as independent contractors and dependent contractors.

For these non-employees, their hours of work are not regulated and they are not entitled to any paid leave days. Only those whose job is regulated by a licensing entity would have to follow certain labour standards related to specific aspects of occupational health and safety such as e-hailing drivers (compulsory motor accident insurance, enforced by MOT) and farmers (standard guidelines on handling hazardous agricultural chemicals, enforced by MOHR). There are voluntary schemes to protect contractors against work accidents such as the Self-Employed Employment Injury Scheme (SEEIS) but voluntary take-up and awareness is low. There is also no regulation mandating take-up or top-down enrolment into schemes for broader risks such as unemployment or ageing/retirement, though there are voluntary programs like EPF’s i-Saraan which similarly see very low take-up.

Updating legislation to ensure fair working conditions

The changing employment landscape caused by rapid digital transformation and hiring practices has exposed massive gaps in current laws on working conditions. The following sections will discuss these shortcomings and potential policy ideas to tackle them.

Hours of work

Despite having maximum working hours of 48 hours a week, overworking remains prevalent among workers in Malaysia. According to a KRI study, about half of all workers spent more than the maximum weekly hours working, especially those in mining, administrative, and support services sectors. In 2020, the capital city Kuala Lumpur was ranked the fourth most overworked city in the world.

Regulating hours of work is mainly applicable for full-time employees that engage in shift work, which can be easily tracked unlike employees that engage in non-shift work. For these shift workers, the government currently permits up to 104 hours of overtime work every month, significantly lenient compared to the 12 hours a week limit (equivalent to 48 hours a month) endorsed by the ILO Hours of Work (Industry) Convention 1919. There is also an issue of enforcement; there have been cases of workers doing overtime without being paid the legally mandated overtime rate as reported by the Ethical Trading Initiative.

Meanwhile, be they full-time employees, independent contractors or dependent contractors, workers engaging in non-shift work face a greater risk of working excessive hours in order to complete deliverables or meet employer/client expectations. Work fatigue caused by working excessive hours heightens the risk of work-related accidents and health issues. Yet, it would be difficult to impose working hours regulations on non-shift workers due to the practicalities in time tracking as well as the workers’ own preferences.

Policy recommendations

To ensure safety against work exhaustion for shift workers, the maximum hours for overtime should be brought in line with, or closer to, the ILO recommendation – not only in number of hours but also instituting weekly limits rather than monthly limits. A safe whistleblower channel for reporting involuntary or underpaid overtime work should also be made accessible for all employees, including migrant workers.

For non-shift full-time employees and for dependent contractors, the government most likely cannot regulate their hours of work as it would be tough to track and enforce. For dependent contractors, it could also take away their job flexibility which is an attractive and preferred aspect of their job for many. That said, the government can safeguard such workers against practices that lead to overworking. Non-shift workers should also be able to access a safe whistleblower channel to report systematic or pressured overworking. Fatigue monitoring features or periodical algorithm audits can be made mandatory for companies reliant on dependent contractors, such as gig platforms, to avoid encoding overwork into the platform.

Independent contractors are usually assumed to have sufficient means and capacity to negotiate their working hours, as they have the highest degree of job autonomy and control. However, the government can still introduce legal safeguards into contract laws against involuntary overtime work, such as voiding hidden clauses or terms set by clients to compel independent contractors to work during unusual hours.

Paid leave days

Currently, only full-time employees are entitled to have a minimum of 21 paid leave days (which includes 13 days of paid public holidays), 14 days of sick leave and 60 days of hospitalisation leave in a year. Female employees have 60 consecutive days of maternity leave though this is still less than the minimum of 98 days recommended by the ILO Maternity Protection Convention. Paternity leave and childcare leave is not provided for in Malaysian law and a study by WAO has also highlighted that these are not widely granted by companies voluntarily.

By law, non-employees like dependent contractors and independent contractors are not entitled to any paid leave days regardless of hours worked.

Too many holidays?

Contrary to the popular perception that Malaysia has too many holidays, a KRI study shows that paid leave days in Malaysia are about the same as other countries if not less. Some examples: Singapore (18 days), Vietnam (22 days), Indonesia (27 days) and South Korea (30 days).

Policy recommendations

Workers of any employment category should be able to earn paid leave days in exchange for serving an accumulated number of working hours, though implementing this practice would be quite challenging for certain jobs.

Nevertheless, some examples of fair or desirable paid leave policy could be more straightforward; for instance maternity leave should get closer to the 98 days recommended by ILO. Paternity leave and childcare leave should be instituted to promote shared responsibilities in caregiving between parents.

For dependent contractors and independent contractors, the provision of paid leave days is operationally challenging because of the flexible nature of their jobs. For dependent contractors, a policy of ‘earned leave’ could be trialled out, much like qualifying for perks with accumulated hours worked or tasks performed, particularly for gig platform workers. For independent contractors, instead of mandating paid leave days, the government could establish guidelines of minimum employment terms in contract law that outlines recommended number of paid leave days commensurate with the tenure of the contract.

Occupational safety and health

There has been a decrease in fatal and non-fatal occupational injuries since the 1980s. Nevertheless, construction site accidents, hazardous working conditions in manufacturing factories, work accidents involving delivery riders and other occupational safety and health (OSH) issues are still frequently reported. One reason contributing to work accidents is the reduced capacity in law enforcement, specifically the National OSH Council that is responsible to set and monitor labour standards concerning OSH matters for various jobs and industries.

Between 2010 and 2020, the operating budget for the Ministry of Human Resources (MOHR) has increased from RM582.39 million to RM834.73 million and the number of employed persons has jumped from 11.90 million people to 15.22 million people. Yet, the number of public service workers for the OSH department under the MOHR has decreased from 1,855 people to 1,692 people during the same time. Using the public service worker headcount as a proxy for the government’s enforcement capacity, the OSH department is severely understaffed.

Moreover, there are new aspects of workplace safety and health matters which are excluded from the existing OSH regulatory framework, such as sexual harassment, mental burnout, worker vaccination, accidents while remote working and more.

Meanwhile, there are few regulations on OSH issues for non-employees. Workplace safety and health guidelines for specific occupations or sectors which cover both employees and non-employees are set by very few bodies like the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) and the Land Public Transport Agency (APAD), if at all.

A similar exclusion problem between employees and non-employees is also exemplified by the implementation of worker vaccination programs via the Program Imunisasi Industri Covid-19 Kerjasama Awam-Swasta (PIKAS). While the vaccination costs of employees in essential industries (i.e. agriculture, construction, manufacturing, plantation, retail) are subsidised by their employers, many non-employees working in essential services sectors, such as e-hailers, delivery riders and contract hospital cleaners have not been similarly fast-tracked nor subsidised.

Policy recommendations

At the minimum, sufficient funds and human resources should be allocated to ensure the enforcement capacity of the National OSH Council and the relevant enforcement body in conducting frequent labour inspections.

The government should make the national insurance against employment injuries (i.e. SOCSO) mandatory for all workers, regardless of their employment status. The scope of SOCSO coverage should be revised to address some of the emerging OSH issues, such as mental burnout and accidents while remote working.

With sexual harassment becoming an increasing concern, the government should review the existing labour laws and the role of the National OSH Council in shaping a safe working environment. If the government intends to introduce an Anti-Sexual Harassment Act, the National OSH Council should be included to support the enforcement of the act.

Worker accommodation

Whether it is for local workers or migrant workers, Malaysia’s current worker accommodation guidelines are severely inadequate. The past reports on the state of housing accommodation for workers indicated an average of 10 workers fitting into a room of approximately 800 to 900 square feet although sometimes 16 to 24 workers can be found in a unit. The Health Director-General Tan Sri Dr Noor Hisham Abdullah has even pointed to the dire and crowded living conditions* as a major factor for COVID-19 outbreaks at workplaces, such as wet markets, manufacturing factories and construction sites.

*Note: We had previously discussed the poor living conditions of the workers’ accommodation in our past article.

Policy recommendations

Setting safe and humane workers’ housing standards for all eligible workers.

The stark difference in the multi-person accommodation guidelines between the Workers’ Minimum Standard of Housing and Amenities (Amendment) Bill and the Selangor student hostel guidelines suggests that the living space standards for workers should be more adequate and humane. The government should refine the minimum housing standards to treat all workers the same. According to the ILO’s Workers’ Housing Recommendation Convention 1961, reasonable minimum living space per person and access to basic amenities (i.e. electricity, water, sanitary facilities) should be established and specified to ensure an adequate living environment for workers.

What about ‘off-the-job’ risks?

So, what about measures to protect against major uncertainties such as unemployment or obsolete skills? Or uncertainties related to life-cycle events such as illness and ageing? Should provisions against these risks also count towards ‘fair working conditions’

These broad risks affect everyone, not only workers. In fact, the current approach of having laws and initiatives based on outdated employment classification excludes those who do not belong to any category. To plug the coverage gap, we argue for an integrated national social protection system for all, which comprises a universal social safety net, a national social and health insurance and an integrated reskilling policy rather than tying these to employment status as is currently the case.

These policies go beyond a Fair Work Act and speaks to a large-scale rethink of our country’s social protection system, with universal coverage. The pandemic has exposed deep gaps in our current patchwork of social safety nets and talk of comprehensive reforms is becoming more widespread, being taken up even by the central bank. Such reforms should come hand in hand with legislation that defines fair working terms for all employment categories as well.

How should we define fair contracts? We will discuss this in the next instalment of this research series.

Email us your views or suggestions at editorial@centre.my

The Centre is a centrist think tank driven by research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas. We are a not-for-profit and a mostly remote working organisation.