Research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas.

The Case for A Fair Work Act, Part 1

Responding to Malaysia’s Changing Employment Landscape

The government is mulling new legislation to ensure the welfare of gig workers. In Part 1 of this research series, we argue for first clarifying what ‘gig work’ covers and for having laws that define what fair work means for all workers.

By Edwin Goh & Nelleita Omar15 April 2021

Baca Versi BM

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, rapid digital transformation and new business models had been changing the nature of work across the globe. More and more informal jobs were being created, characterised by one-off tasks, work-hour flexibility and low barriers of entry. In Malaysia, these jobs include but are not limited to ‘gigs’ on platforms such as Grab, Foodpanda and GoGet, to name a few.

The rise of these jobs has yet to be reflected in official employment statistics. In Malaysia, being an ‘employee’ as reported by DOSM is still the largest and most stable employment status, hovering at around 75% of the total workforce over the last 20 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Employment Status* Trend, 1999 to 2019

*DOSM Employment Status definitions:

Employee – A person who works for a private employer and receives regular remuneration in wages, salary, commission, tips or payment in kind.

Own-account worker – A person who operates his own farm, business, or trade without employing any paid workers in the conduct of his farm, trade or business.

Unpaid family worker – A person who works without pay or wages on a farm, business or trade operated by another member of the family.

Employer – A person who operates a business, plantation or other trade and employs one or more workers to help him.

These statistics mask two significant issues regarding employment in Malaysia. The first issue is the unclear extent of informal employment. At a quick glance, the above classification could give the impression that the majority of the workforce is in formal full-time employment.

The fact is, an unknown or unpublished proportion of the ‘employees’ above are informal workers, i.e. a person who works for a private employer, receives some form of remuneration, but is likely not covered by any contract, social protection schemes, benefits or employee rights. Informal worker estimates have to rely on rough proxies – approximately 62% of the workforce if we go by EPF coverage.

The second issue obscured by employment statistics is the changing nature of informal work itself. There have been increasing examples of informalisation occurring in Malaysia, from the growth of gig platform work, to the growth of remote digital work, to the shift from open-ended employment contracts to temporary or project-based contracts. According to Malaysia’s 2021 Economic Outlook Review, this purported ‘gig economy’ is a new growth area. However, whether these workers are micro-entrepreneurs or a new type of informal worker has yet to be settled or even discussed adequately.

What Does The ‘Gig Economy’ Mean?

Food delivery riders and e-hailing drivers are among the jobs most frequently associated with the term gig work. What about AirBNB hosts? Freelancers who sell their services on Fiverr or Upwork? Taking it further, are farmers and fishermen who sell their produce online gig workers too?

Why is this important? The terms ‘gig economy’ and ‘gig worker’ as used in speeches, media and even policy documents today have come to cover an unwieldy range of job types and most importantly, very different employment relationships. While we agree that there is a need to address issues faced by gig workers, we also hold that policymakers first need to clarify who they are.

We also argue that in the effort of clarifying who they are, current concepts and frameworks related to employment status are in need of major updating.

What makes a so-called gig worker different from older terms for informal employees, whether ‘firm-based’ terms (e.g. self-employed, freelancer, microentrepreneur, solopreneur) or ‘worker-based’ terms (e.g. temporary or casual workers)? We posit that the difference is in the power relationship between the worker and the employer* or employment vehicle. In fact, we argue that the power relationship between the worker and any employment vehicle or entity should be a core criteria in designing new worker legislation and policies.

*Note: From this point, ‘employer’ is used as a broad shorthand (and not a legal term), representing the party that either employs the worker or is the intermediary for the supply of jobs.

Employment power relationships is the key

The power relationship between employer and worker is comprised of the degree of control exercised by the employer over working conditions as well as the worker’s degree of dependency on the employer for survival or livelihood. This framework was proposed in a July 2020 paper by the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose as a way to understand today’s employment power relationships and as a framework to classify employment status (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Employment Power Relationship Framework

Workers who face a high degree of employer control over many key job aspects (such as working hours, maximum take-home pay and reporting) and who relies greatly on the employer (for example for the bulk of take-home pay) is effectively an employee, regardless of whether there is a formal agreement.

Conversely, workers who face little or no employer control over their job and who are not tied to a single employer for the bulk of their earned income, are effectively independent contractors.

It is the workers who fall between these two categories of ‘employee’ and ‘independent contractor’ that present the greatest policy challenge today. Termed ‘reliant’ or ‘dependent’ contractors by the UCL researchers, the power relationship experienced by these workers are not depicted nor understood very clearly today, which can lead to inappropriate labelling or categorisation.

Viewing employment status through the lens of power relationships means that the way we categorise workers needs to go deeper than numbers of hours worked, type of contract or occupational definitions. Workers who perform the same job activity may not necessarily have the same employment status as there could be different levels of control and dependence governing the job.

Take the example of delivery riders. Those who are hired by a courier company that imposes strict conditions on working hours, notice period, freedom to be employed elsewhere, and other job parameters which restrict autonomy and the capacity to diversify income should really be classified as ‘employees’ due to the degree of control and reliance present.

Delivery riders who get jobs by directly offering their services to customers, be it by advertising on physical posters or a Facebook page, are essentially ‘independent contractors’ with high control over most facets of their work. On the other hand, delivery riders who get jobs via a gig platform company that control certain but not all aspects of the job such as task allocation, access to the end customer, attire and others, are arguably better described as ‘dependent contractors’.

Applying the power relationship lens to jobs that are commonly associated with the ‘gig economy’ today shows the wide range of power relationships possible for the same job activity (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Typical ‘Gig’ Jobs vs. Possible Employment Status (Illustration)

Knowing the job’s underlying power relationship is important because different power relationships produce different worker needs and issues. Understanding power relationships is also crucial in deciding the split of responsibility between the worker, the employer and the government.

For full-time employees, it is clear that the employer needs to ensure enrolment and contributions into social protection schemes, but what about for dependent contractors? Should the onus really be on the worker as is the case for independent contractors?

This question of what is a fair level of workers’ rights and benefits in exchange for a degree of control (and who provides them) is why we are advocating for a back-to-first-principles conversation about employment status and ultimately, the promulgation of a Fair Work Act.

From power relationships to Fair Work

Why a ‘Fair Work Act’ and not a ‘Gig Worker Act’ as is reportedly being contemplated by the government? Above, we argued for the need to first understand the major power relationships of today’s employment landscape. The second major argument for a broader ‘Fair Work Act’ is the adequacy of current legislation. Can Malaysia’s current laws adequately express what are fair conditions for the different employment power relationships prevalent today? In our view, not without significant modification.

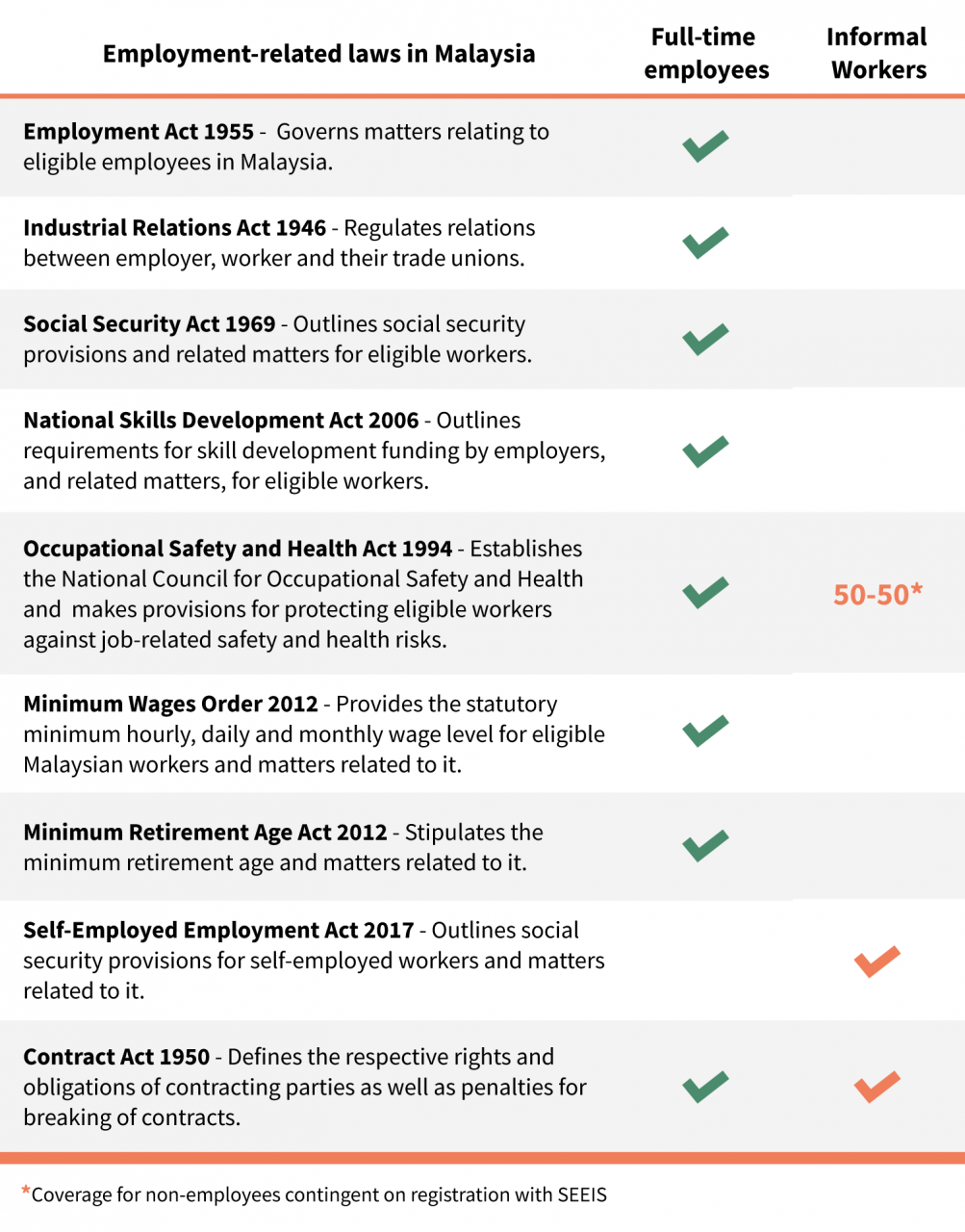

Firstly, the two worker classifications in existence today are insufficient. Today, you are either a formal employee (full-time or part-time*) governed by the Employment Act 1955 and other related legislation or a contractor reliant on the Self-Employed Employment Act 2017 and the Contracts Act 1950 (Figure 4). There is yet a classification that captures the distinct power relationship of a third but growing class of workers i.e. dependent contractors.

*Note: Although current laws and regulations do cover part-time employees, the designation is difficult to enforce in practice.

Figure 4: Current Laws Applicable To Malaysian Workers

Secondly, the premise of employment status and legislation today hinges too much on formalisation, i.e. whether one has a contract of employment or is registered as self-employed. Having an understanding of employment status based on a test of employer control and worker dependence would be a truer way of classifying workers rather than whether or not an employment contract exists (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Definition Of ‘Employee’ Comparison

Malaysia should take care to avoid major classification pitfalls. By applying the lens of power relationships to employment classification, we can have a more grounded and structured understanding of the range of employment status today. More importantly, with a clear understanding of the different power relationships underlying key employment classes, we can also have a more honest discussion of what is fairly owed to different types of workers by employers vs. the government.

Which brings us to the next question, namely what are fair work conditions for they key categories of employment power relationships? As a reference, we looked to the Oxford Internet Institute’s Fair Work Initiative which outlines five core principles of fair work: fair pay, fair working conditions, fair contracts, fair management and fair representation (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Fair Work Principles

Putting together fair work principles and the power relationship framework enables policymakers to prescribe employment regulations best suited to the characteristics of each employment classification. What are minimum ‘fair work’ provisions owed to employees, whether formal or informal? What are minimum ‘fair work’ provisions owed to independent contractors vs. dependent contractors?

In subsequent instalments of this research series, we will propose examples of what fair work principles could look like for the three major employment classifications we’ve proposed namely, employee, independent contractor and dependent contractor.

Updated laws need updated policy frameworks

At the time of writing, countries including France, Spain, and the Netherlands have reclassified some informal gig workers as employees. However, the grounds for classification are not the same across these jurisdictions – the judgements very much depend on local definitions of ‘employee’, ‘contractor’ and ‘gig worker’, amongst other factors. In some cases, having overly broad definitions for ‘gig worker’ led to unanticipated consequences; in the case of California for example, many freelancers lost their job after the passing of AB 5, as their ‘employers’ could not afford to reclassify them as employees as mandated by the new law (which has since been overturned).

Malaysia should heed and extract the right lessons from these court rulings. The key policy decision is not whether to formalise workers or whether to have specific gig worker legislation. Rather, it is to clarify how we’re thinking about employment classification, in ways that capture the evolving dynamics of employment in Malaysia. Only in this way can we adequately fix or bridge the gaps in our current laws to ensure fair work for workers today and to address those left behind.

The landmark UK Supreme Court ruling on Uber in February this year provides an instructive example of employment classification based on (i) power relationships and (ii) transcending the employee-vs.-independent contractor dichotomy.

Following a suit brought by a group of ex-Uber e-hailers, the UK Supreme Court ruled to reclassify a group of 40,000 Uber UK drivers as “workers” entitled to minimum wage, holiday pay and other benefits, due to the management practices imposed on the workers at the time, such as inability to negotiate fares and access job details before they accept the job. Two aspects of this ruling should be noted:

(i) The importance of underlying power relationships. The ruling applied only to a specific group of Uber e-hailing drivers who worked with Uber before 2016 which experienced company policies resulting in lower job autonomy compared to later groups of Uber drivers.

(ii) A ‘third’ classification. The ruling classified the affected e-hailing drivers as ‘workers’, a designation that reflects a higher degree of flexibility relative to ‘employees’. Nevertheless, this designation still comes with its set of rights and benefits as articulated by the UK’s labour laws.

How do we define fair pay for each employment classification? Stay tuned for the next instalment of this research series.

The Centre is a centrist think tank driven by research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas. We are a not-for-profit and a mostly remote working organisation.