Research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas.

Can Everyone Really Reskill Themselves?

We asked this and more in our study on non-graduate informal workers’ aspirations with a focus on delivery riders.

By Edwin Goh & Nelleita Omar11 November 2020

Reskilling, upskilling and cross-skilling have become policy buzzwords in recent times. The recent Budget 2021 continued this emphasis in training the workforce by announcing allocations totalling over RM19 billion, to be delivered via various programs by a wide range of agencies from MDEC to PUNB.

This is a generous allocation, but are allocations for course provision adequate? Through our recent research, it became clear that course provision needs to be accompanied with complementary measures that enable access.

As we outline in our illustrated piece below, a person’s background and circumstances significantly determine whether they can or will access available programs.

Meet Aiman*

*Fictional character Aiman is inspired by our interviews with non-graduate informal workers as well as our study findings.

Aiman is a 28-year-old assembly line worker at a factory in Selangor. He holds an SPM certificate. He earns RM1800 a month which barely covers his family’s living expenses. His wife stays home to look after their two children as reliable childcare is costly.

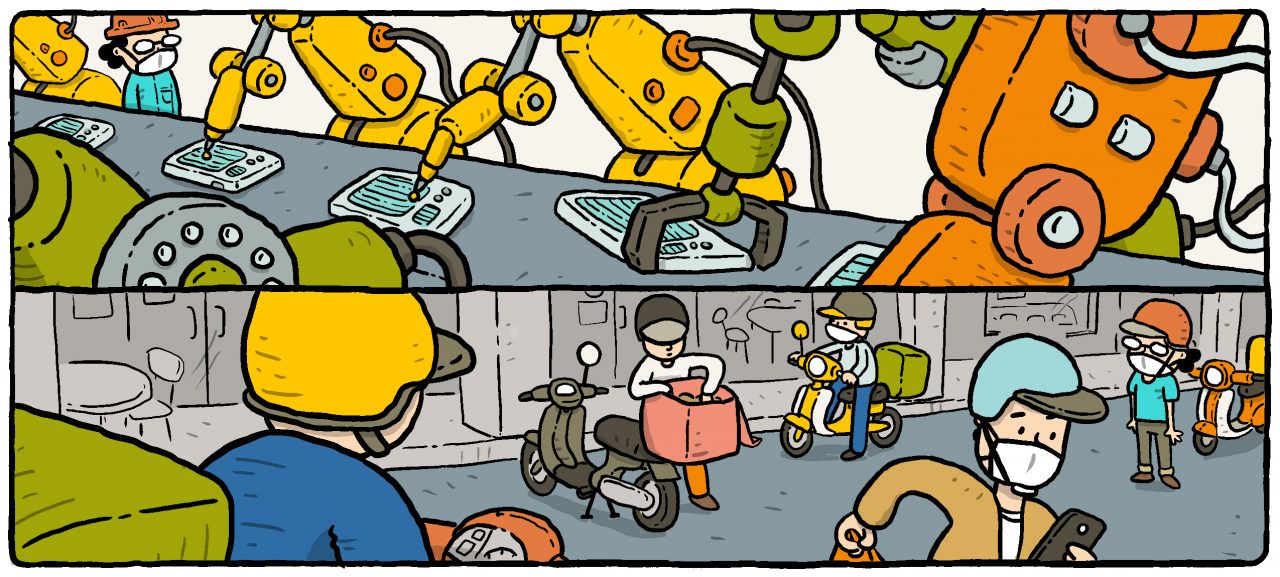

To make ends meet, he does gig work as a delivery rider after his factory working hours. He usually comes home late at night and sleeps for a few hours before going to the next day’s factory shift.

The factory’s sales have been very unstable due to the tough Covid-19 economy. As a result, Aiman’s shifts have been reduced. It was a matter of time anyway — Aiman knows that the factory has been planning to replace some manual tasks with machines.

To make up the lost income, Aiman started putting more hours into delivery gig work. But since the MCO, more people have started doing delivery gig work, even people with higher educational qualifications. More people fighting for the same jobs means longer hours.

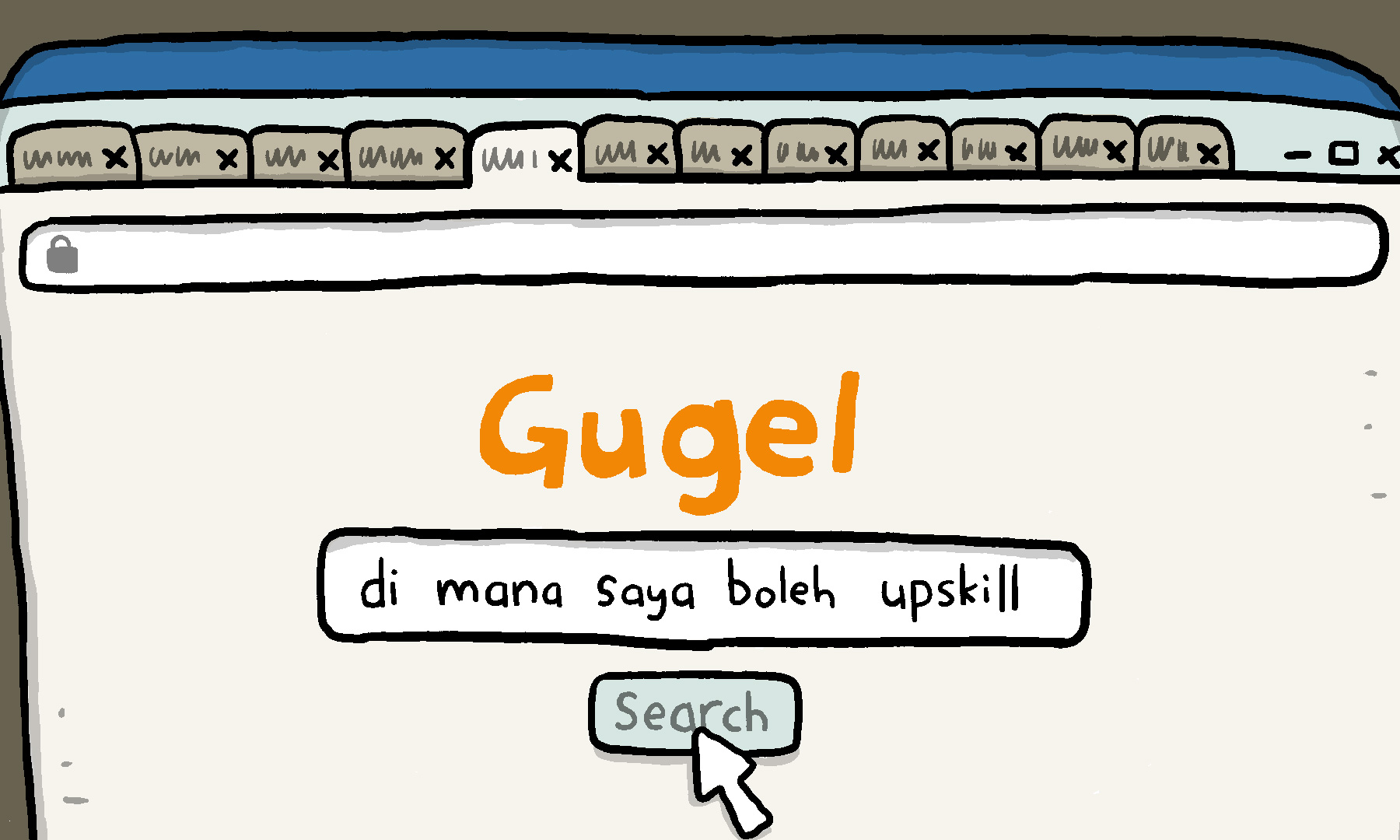

Aiman knows that he can’t do these jobs forever. He sees words like ‘reskilling’ but it feels like they’re only for privileged people – people who speak English, people who work with computers, people who can apply what they learn online. Even if there are suitable programs for him, he does not know how to find them – there’s a lot of information out there, but very little guidance. His family and social circles can’t really help him much either.

Aiman wants to do better for the sake of his family but he can’t see too far into the future. He needs to focus on surviving now. Taking time out to reskill himself is also very risky – will he really get a better job at the end? Can he afford to pay for the course? What happens to his income and his family in the meantime?

Until these questions are answered, Aiman will keep on doing low-wage jobs that come his way.

Understanding the challenges

Malaysia has an extensive skills development ecosystem with various program offerings and funding options. For workers from backgrounds like Aiman’s however, extensive does not mean accessible. There are several challenges that stand in the way of accessing available opportunities.

High risk and opportunity cost

Taking time out to reskill means cutting back working hours and forgoing much needed income. Even if the reskilling program is flexible in terms of hours, cutting income is too much of an opportunity cost for low-waged workers especially when there is very little savings buffer. And not all informal workers are eligible for training allowances (more on this below).

The uncertainty of going for reskilling is also a deterring factor. Not all programs offer job placements or have a known track record in developing sustainable micro-entrepreneurs. There are no guarantees for anyone of course, but the risk of uncertain outcomes for those with low incomes and little savings are even greater.

One of the top factors in accessing a reskilling program is income replacement. 88% of study respondents want a training allowance to replace their lost income during the program duration. Certainty is important too; 87% respondents said that having a guaranteed job opportunity is important or very important to them when considering to join any training program.

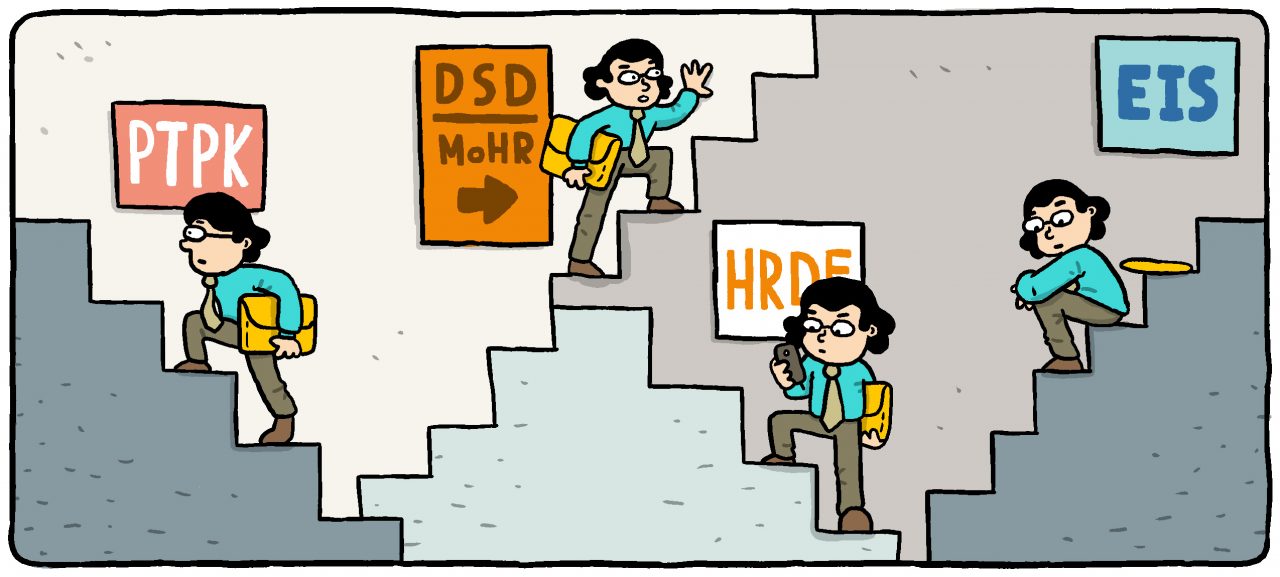

Limited eligibility for funding options

Not all informal workers can access the funding options on offer. PTPK loans are only applicable to full-time programmes approved by the Department of Skill Development (DSD) under the Ministry of Human Resources. Only workers under HRDF-registered companies can access HRDF funds, with their employer’s approval. The training subsidy and allowance provided by EIS Centre are only available for EIS contributors. In other words, a large share of informal workers will not have access to key sources of training funds on offer today.

In our latest study, 58% of the non-graduates who participated in training or reskilling before had paid for their training fee themselves. 19% was covered by a government agency while 14% was covered by their employer.

Ecosystem difficult to navigate

The ability to access reskilling opportunities depend in large part on whether one can navigate the information available to find programs that best fit their needs and interests. Workers who are digitally savvy and proficient in English are more advantaged in this respect. Those who are not as savvy will be challenged by the various landing pages and registration portals scattered across multiple agency and training provider websites.

Our recent study found that 78% of respondents are interested or very interested in reskilling but only 30% have participated in a program. Over half of those who have not participated in any reskilling program say they do not know where or how to access the training courses. In interviews with respondents, we found that non-graduates from well-educated middle-income families were more comfortable and proficient in searching for reskilling opportunities online.

Weak career guidance and social capital support

Unlike graduates, most non-degree holders have never had access to career counselling or guidance to learn about available career options. And unlike those from higher-income backgrounds, their social capital – such as family members or friends – are not as able to connect them to good work, training or mentoring opportunities.

Only 30% of respondents in our study comprising non-degree holders have received career counselling whereas more than two-thirds say they would like to receive professional career advice and guidance.

Lack of attention to segment’s needs and interests

In line with the drive to digitalise the economy, particularly in light of COVID-19, reskilling programs that focus on digital skills have received much policy emphasis. Digital skills such as digital marketing, coding and programming may be of interest to some non-graduates (or even graduates) but for many, it may not be easily translated into an income-generating avenue. Many of these programs also presume a minimum level of comfort with online learning as well as English proficiency.

Two-thirds of survey respondents said that they would take up reskilling to ‘be their own boss’, either to become a freelancer or to set up a small business. 71% of respondents expressed preference for apprenticeship programs, with Bahasa Malaysia as the main language of instruction.

Conclusion

The age of digitalisation could exacerbate today’s inequalities. To ensure social mobility for all in this era, policymakers must go the extra mile to ensure everyone, particularly from less privileged backgrounds, can access available reskilling opportunities.

Policymakers need to understand the different demographics’ opportunity costs, learning capacities, interests and language proficiencies to ensure that programs and allocations for reskilling really reach those who need it the most. Providing reskilling courses is one component of the solution; supporting measures such as information organisation, course curation, simpler funding options, and guidance also need to be in place.

Email us your views or suggestions at editorial@centre.my

The Centre is a centrist think tank driven by research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas. We are a not-for-profit and a mostly remote working organisation.