Research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas.

Getting Around: Towards a Decent Daily Commute

Adoption of public transport is still relatively low in Klang Valley and other metro areas. What are the key issues we face in commuting by public transport? We summarise the main problems, propose some solutions and suggest some minimum standards.

By Aziff Azuddin & Nelleita Omar2 September 2019

Introduction

- For a significant number of people, commuting daily to work is an inescapable fact of life. Commuting or transportation costs for Klang Valley is estimated to take up 20% to 30% of total monthly expenses, according to EPF’s reference budget Belanjawanku.

- Long-term investment in city transport infrastructure like the LRT & MRT network is much needed. Near-term efforts to reduce commuting costs such as the recently introduced Klang Valley unlimited travel pass is also positive. But apart from purely financial costs, there are other costs to take into account such as the time spent commuting, the stress caused and the impact on the environment.

- As urban sprawl pushes affordable housing further away from KL’s centre, the cost, time, stress and environmental impact associated with commuting will become an increasingly important issue in the future. This case study aims to highlight key issues in the commuting experience today, towards advocating a set of standards for having a decent commute in the Klang Valley and other major cities in Malaysia.

Current State of Commuting

- We agree with the premise that good public transportation is the most sustainable mode of commuting overall. However, according to the World Bank, in 2015 only 17% of KL commuters use public transportation compared to 62% in Singapore and 89% in Hong Kong. Similarly, a study by Uber and BCG showed that only under 15% of KL is travelled using public transportation.

- These findings, not to mention today’s traffic conditions, point to the fact that most people in the Klang Valley are driving to work. The average rate of car ownership in Klang Valley is two cars per person (p2 in linked report). This is perhaps unsurprising as the development of Klang Valley’s metro-rail network only began in the late 90s, with several planning issues resulting in lack of integration and connectivity. Malaysia’s policies also appears more inclined towards car ownership, with the government emphasis on developing a Malaysian automotive manufacturing industry.

- Clearly, more commuters will need to switch from cars to public transportation. Apart from the costs associated with driving, there are time costs (Malaysians spend an average of 53 minutes stuck in traffic) as well as costs related to urban and environmental sustainability (transportation is the second highest energy consumer in Malaysia after electric power generation).

- Encouraging switching seems to be on the government’s agenda; aside from the Klang Valley unlimited travel pass mentioned earlier, the government launched a RM500 million fund in May this year to encourage public transportation adoption.

- Nevertheless, to achieve the government’s target of increasing the modal share of public transport to 40%, more effective responses are needed to address all the costs, hassles and frictions associated with switching to public transport. Or framing it another way, more effective responses are needed to produce consistent and comfortable commuting experiences.

- This short study sets out to propose some responses towards delivering better standards in public transport commuting. This study is informed by interviews with commuters and literature research on some of the biggest public transport costs and frictions faced by city commuters.

- A note on methodology: this is not a quantitative study and does not claim to represent the exact size or prevalence of the issues. However, based on the overlap between interview responses, personal experience and literature research (including social media posts), we conclude that there are three major sources of costs and frictions to resolve: first mile-last mile connectivity, service reliability and route adequacy.

- These issues have been discussed elsewhere, but in this piece we take stock of current thinking and advance some policy initiatives towards achieving some minimum standards in public transport commuting.

1. First Mile-Last Mile Connectivity

- First mile-last mile connectivity here refers to the mode of transport or connection to reach the closest metro-rail station. To make full use of the multi-billion ringgit investments in the LRT, MRT and KTM networks, the trip to the nearest or most practical metro-rail station needs to be affordable and relatively short. Yet, many commuters do not have proper access to affordable first mile-last mile solutions; either their areas are underserved or available services are infrequent and unreliable.

- First mile-last mile connections are typically buses, e-hailing services and taxis. Cycling and walking also fall under this category if you live close enough to the station.

- Feeder buses are the main service providers for first mile-last mile connections though e-hailing services are increasingly used as a solution as well. However, according to SPAD (the precursor to APAD), the feeder bus system face limited resources, which affects frequency and route coverage.

Current Direction

- The Minister of Transportation Anthony Loke has stated that the government will collaborate with local councils, feeder bus operators and e-hailing services to resolve the first mile-last mile connection issue though to date no specific measures has been announced. RapidKL however, recently announced implementing a trial run of minibuses to cover areas not reachable by its larger vehicles.

- Meanwhile, the Finance Minister’s political secretary Tony Pua has mentioned that Putrajaya is currently in talks with e-hailing service Grab to provide first-mile connection.

- One key approach towards resolving first mile-last mile connectivity appears to be Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) i.e. encouraging mixed commercial and residential development along existing or future MRT stations. Whereas this is good for new areas, mature areas will still need solutions that work with the way the neighbourhood is laid out.

"Why should you provide feeder buses if you can work with Grab? They can actually arrive and give door-to-door delivery from the MRT to commuters’ homes at a reasonable price, and at a cost that will be cheaper than us (the government) supplying feeder buses."

Tony Pua, Political Secretary to the Minister of Finance

- E-hailing as a solution for first mile-last mile connectivity might relieve costs for the government, but there is no guarantee that it would be affordable for lower income commuters unless there is some cost-sharing. Adding to the issue is the uncertainty in e-hailing prices and driver availability with the full implementation of the PSV license by 12 October this year, after the deadline was extended by the Ministry of Transportation.

- Interestingly, a small town in Canada had piloted e-hailing as a solution to public transportation problems. The experience of Innisfil shows some of the issues that arose from the pilot, including the higher cost of subsidising ride-sharing services compared to establishing feeder bus services.

Policy Considerations

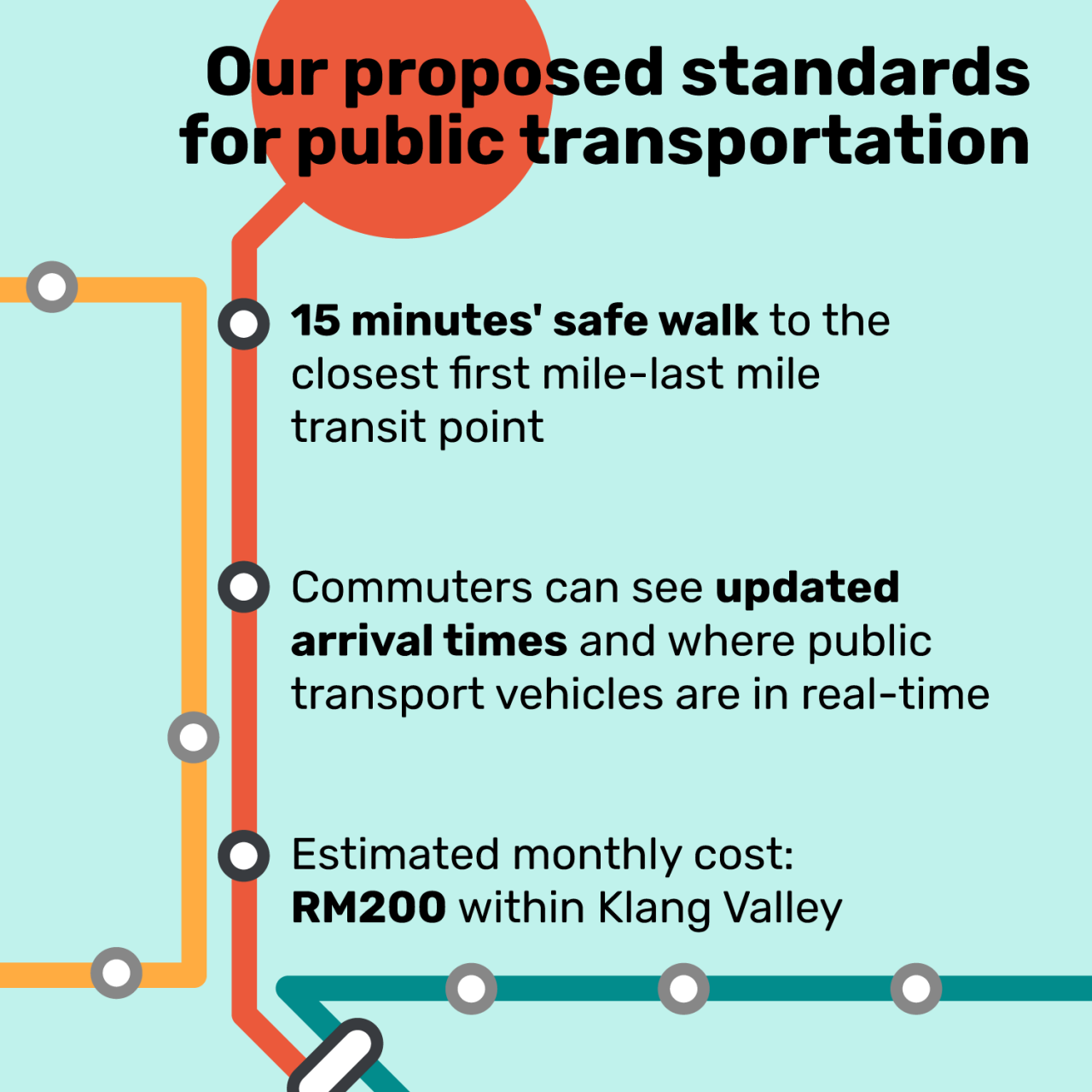

- What might be decent standards in the case of first mile-last mile connectivity? A 2018 Penang study showed that commuters were willing to walk for around 13 minutes or 600 metres to reach the closest bus station if walkway conditions were safe and accessible. Given this, perhaps we should aim for having the nearest public transport point, such as a bus stop, to be no more than a 15 minutes’ safe walk away from a person’s home.

- What about the trip from the bus stop to the next destination, say the LRT or MRT station? Good public transportation for this leg should be reliable and affordable. But if the feeder bus system is limited by budgetary resources, as maintained by the authorities, what can be done to deliver these first mile-last mile needs?

Share first mile-last mile demand data

- What if commuters could indicate their first mile-last mile needs and ride-share scheduled vehicles with other commuters? This was the premise of initiatives such as Beeline and GrabShuttle in Singapore as well as Uber Bus in select cities in Egypt. In 2017, a similar carpooling pilot, called GrabShare was tested in Malaysia though the service has since been put on hold for improvement purposes. This is similar to another Malaysian carpooling initiative, Tumpang which was launched in 2015 but has since gone defunct.

- Throughout cities in the United States, commuting platforms are allowing communities to take part in first mile-last mile crowdsourcing where people submit route suggestions, drop-off points and schedules. Enough votes for a route or schedule would confirm and charter the service.

- Since first mile-last mile connectivity is needed to increase usage of public transport, we take the position that providing first mile-last mile demand data is a public good and should be funded (or otherwise facilitated) by the government. The data would provide feeder bus companies better insight into high-demand routes and times, reducing the problem of empty buses and wasted resources. The data would also provide valuable information to other types of transport services, who could then compete to ply those routes.

Enable a range of innovative service providers

- Not all routes or housing areas can be serviced by large feeder buses. And not all routes can satisfy both demand and profits, such as in low-income areas. Giving access to first mile-last mile demand data is a needed step, but subsidising and facilitating different types of solutions is also needed particularly for community-driven initiatives. The RM500 million public transport adoption fund set up by the government could be used to pilot such community-driven initiatives wherever needed, allowing solutions to surface from the ground up.

2. Reliability

- The unreliability of both feeder bus and KTM services are often mentioned in studies and surveys on Malaysian public transportation. A study on Putrajaya bus services, for example, showed that many commuters faced infrequent service, lack of punctuality and lack of information on routes or schedules.

- A similar issue plagues the KTM, as shown by this study investigating the railway service. The KTM also has appears to have communication issues; commuters are frequently not informed of delays and disruptions ahead of time, with no replacement or alternative services offered.

L, 32, stays in Rawang. For L, the feeder buses would often come at unpredictable times and would sometimes reduce service frequency without warning commuters beforehand. It is L’s only mode of transportation to work, as the bus company is the only public transport mode servicing L’s area.

AS, 29, leaves home early to catch a specific KTM train that goes directly to his workplace. Due to current upgrading works, the service frequency is been reduced to once per hour. If a disruption or delay happens, AS is forced to take the infrequent replacement buses and connecting train lines which takes far longer.

- KTMB’s unreliability may stem from years of poor financial performance and a problematic business model. But there also appears to be a lack of accountability for shortfalls in reliability within the various public transportation institutions. For example, on-time performance amongst the various public transport services are not routinely published, nor does it appear to impact budgetary or hiring decisions.

Current Direction

- As far as accountability goes, in 2018 Prasarana was directed to announce delays above 15 minutes under a new standard operating procedure.

- Neither the government nor the respective public transport services has openly discussed plans to publish data related to reliability. However, the Ministry of Transportation does have an existing system that tracks movement of RapidKL buses throughout the Klang Valley in real time. There are also electronic display boards at select transit points to indicate estimated arrival times but this system appears to be unused or does not work as intended.

"All delays involving technical problems in excess of 15 minutes are categorised as ‘major disruption’ and the onus is on Prasarana to provide clarification to the public through a media conference."

Anthony Loke, Minister of Transportation

- Currently, this requirement only extends to the Rapid KL LRT service. The focus is on services provided by Prasarana and not yet for problematic rail services such as the KTM. In 2011, KTM announced that they would refund journeys delayed over 30 minutes. Despite the policy, there is no information on their site, indicating how to engage in this process. This is unlike RapidKL which provides accessible information showing commuters how to seek refunds in cases of delays.

Policy Considerations

- What might be decent standards in the case of public transport reliability? For a significant number of city dwellers who’ve used e-hailing services such as Grab, it is difficult to accept any other standards. This includes relatively consistent frequency of service (for example, a vehicle every 10-15 minutes), real time knowledge of the vehicle’s location as well as relatively on-time arrivals.

- Technology does not appear to be the constraint; financial and operational effectiveness is likely the crux of the issue. And the spur to achieve better levels of financial and operational effectiveness requires greater transparency, particularly information on service reliability.

- To this end, we advocate making scoreboards of transport services’ performance public and open-source. Sites such as Recent Train Times, for example, uses open data to predict and score train punctuality of UK rail services, allowing commuters to know which train services are typically late or on time.

- Making reliability data public would motivate and pressure the various service providers to improve; it would also help to support any government budgetary or investment decisions. This data could also enable independent parties to integrate, utilise and develop the data for useful public-serving applications.

3. Route Adequacy

- Many of the individuals interviewed for this study shared their experience of long commutes and stress caused by multiple transit connections. For those with no other choice, taking multiple modes of transport and having multiple waiting times to complete one journey is just a fact of life. For some, the journey eventually becomes unbearable, compelling them to move closer to public transport stations despite paying more in housing costs. For others, the lack of a direct route, even for relatively short distances, leads them to choose more expensive options such as e-hailing services.

A, 24, used to stay in Subang and commuted to work by Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and two LRT lines, to get to work in KL. This journey of three exchanges would take 1.5 hours each way. This commute forced her to find a property closer to KL despite the higher cost.

N, 44, lives in Bangsar and works in Mont Kiara which is a fairly popular car route. However, N would need to take two buses to complete this short 7km journey. On most days, N takes a Grab in to work.

- The number of transit points is a major source of friction or inconvenience for commuters. Better routes, with minimal transit changes, would encourage people to switch to public transportation as it would decrease the stress of commuting.

Current Direction

- So far, there doesn’t appear to be any specific developments regarding the improvement of routes and reducing multiple transit connections.

Policy Considerations

- What might be decent standards for route adequacy and the number of transit changes? Defining decent standards here is more complex considering the sheer variety of starting points and destinations demanded by commuters, to be balanced against cost-to-service considerations. But the bottom line is, community consultation and involvement in route planning needs to be strengthened in order to make public transportation an attractive option.

- Much like the first mile-last mile connectivity issue, community involvement to improve route planning can be facilitated by sharing transport demand data. The use of technology and digital tools to resolve commuting or urban planning issues is extremely low for a city with Kuala Lumpur’s population density and GDP – this needs to change.

- Looking outside Malaysia, platforms like Remix enable urban transportation planners to visualise, calculate and plan transportation networks in and between respective areas. When combined with crowdsourced information, these tools can enable routes that are more tailored to the various needs of the community.

Conclusion

- Switching from driving to public transportation is the most feasible way to manage transportation costs long-term but only if all the associated hassles and frictions are addressed. To get there, we need to have a set of standards for the public transport commuting experience, one that would encourage the majority of commuters to switch to public transportation.

- The need for these standards becomes more critical as affordable housing moves further and further away from the city centre. A study of Chinese commuters showed that 45 minutes is a tipping point; those with commutes exceeding 45 minutes prefer shortening their journey by moving while those with commutes under 45 minutes are willing to increase travel times for better jobs or homes.

- For many commuters in the Klang Valley however, particularly low-income households, moving to reduce commuting time may not be an option. Making commuting via public transport tolerable, if not enjoyable, should be a priority for any government committed to equitability as well as environmental impact.

- Based on existing research and interviews with commuters, we propose a set of standards for commuting via public transportation in the Klang Valley. This proposed set is meant to provide an initial framework for public discussion; we hope that further studies and pilot projects will provide more representative numbers and supporting details.

- Our main policy recommendations centre around harnessing technology and public participation by crowdsourcing demand data. This requires the government to take on a more facilitating role rather than a command role in designing and providing public transportation services.

- By providing a commuting data platform that involves the public more actively, better local-based solutions will emerge. Progressively, we may become a public transport nation after all.

Note: The now-defunct Land Public Transport Agency (SPAD) website previously held useful resources on transportation in Malaysia. The newly-rebranded APAD website have yet to provide a public archive of these resources; we hope that these resources will be made available in the near future for the public interest.

Other interesting reading:

Commuting Calculator (Ford)

Resolving KL’s traffic woes (Edgeprop.my)

Five reasons why public transportation in Malaysia is more expensive compared to Singapore (Ong Kian Ming)

Improving urban transportation for upward social mobility in Malaysia (World Bank)

Integration is the key (The Star)

Taking the nation to the next level (Focus Malaysia)

Email us your views or suggestions at editorial@centre.my.

The Centre is a centrist think tank driven by research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas. We are a not-for-profit and a mostly remote working organisation.