Research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas.

A Guide to Social Protection in Malaysia

Basic information on the social safety net for every Malaysian.

By Editorial Team18 October 2019

Baca Versi BM

What is social protection?

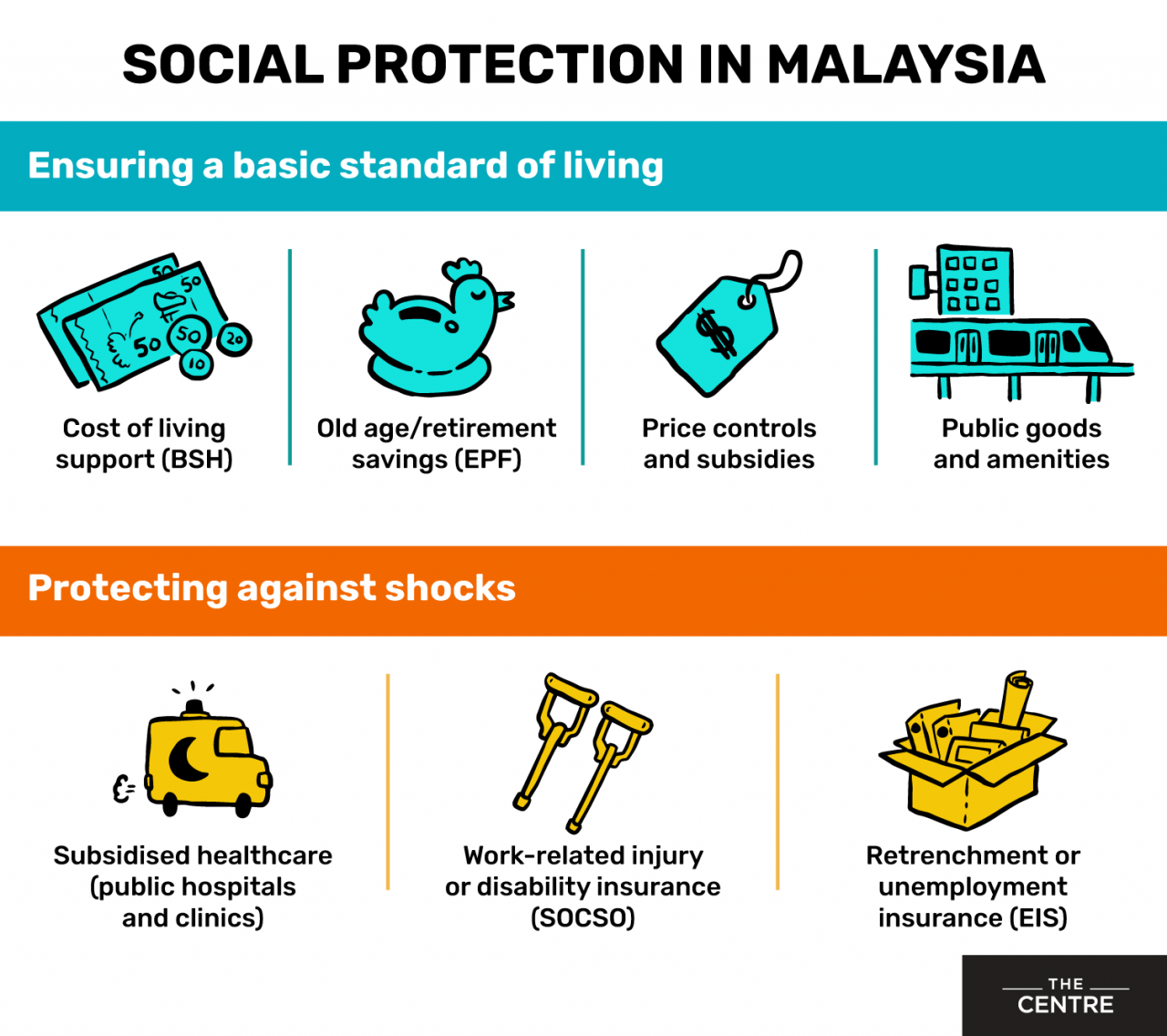

- Broadly, social protection stands for policies, programs and measures aimed at (a) ensuring a basic standard of living for a nation’s people, and (b) protecting people against major shocks such as serious illness, injury and unemployment.

What are the main measures to ensure a basic standard of living?

Income Supplementation

- Bantuan Sara Hidup (BSH), a cash transfer made to eligible recipients throughout the year administered by LHDN. Families earning below RM4,000 a month and individuals earning below RM2,000 a month are covered.

- Skim Bantuan Kebajikan administered by the Malaysian Welfare Department. Households which meet the Department’s criteria as poor or vulnerable are eligible for cash transfers as well as other assistance.

- Main issue: If online surveys are an accurate reflection, most Malaysians want BSH to continue and in fact be widened. More than 900,000 applications have been received for the cash aid since it’s reopening in 2018.

How should the BSH be structured? We raise that question and others in next week’s editorial.

Old Age/Retirement Savings

- The Employee Provident Fund or EPF is a compulsory savings scheme for old age/retirement, with a portion allowed for specific purposes such as education, medical expenses and paying down first-home mortgages.

- All Malaysian private sector employees are covered by the scheme. Employees and their employers are required by law to contribute, respectively, 11% and 12%/13% of the employee’s salary towards an investment fund managed by the federal statutory body also known as EPF.

- Non-Malaysians and self-employed Malaysians can join the scheme voluntarily.

- EPF contributors may withdraw 30% of their savings when they reach 50; those 55 years or older may withdraw all of their savings.

- Main issue: the combination of longer life expectancies, low incomes and low savings means that the majority of EPF contributors do not have enough to retire. As more people become self-employed and as the demand for old age care rises, revolutionary but costly solutions may be required.

Other social protection measures to ensure a basic standard of living include food price controls and petrol subsidies. Public goods such as public education, law enforcement, low-cost housing and public transport can also be considered as types of social protection.

What are the main measures to protect against shocks?

Subsidised Healthcare

- Malaysia has a highly subsidised public healthcare system which co-exists with privately owned hospitals and clinics. Outpatient charges for most non-critical treatments in government institutions are below RM10 whereas equivalent treatments in private hospitals or clinics could run upwards of RM100.

- Malaysia does not have a national health insurance scheme. The closest to a national health insurance scheme in Malaysia is MySalam which provides cash payouts upon diagnosis of certain critical illnesses and hospitalisation allowance in government hospitals for individuals earning up to RM100,000 a year.

- A supplementary pilot scheme called PeKa B40 was launched in April this year, a program for qualifying low-income earners that provides free health screenings and selected financial assistance for treatment of non-communicable diseases such as cancer.

- Main issue: The question of financial sustainability is a major issue, especially with the rise in chronic diseases such as diabetes and cancer, the recognition of mental health as a mainstream issue and an ageing population. A national health insurance scheme has been proposed since the 7th Malaysia Plan, and could be introduced ‘sooner or later’ – watch this space. Meanwhile, MySalam’s funding and program design has come under intense questioning.

Injury and Disability Insurance

- Every employee making below RM3,000 a month must make salary-deducted SOCSO contributions, i.e. premiums towards two insurance schemes: one covering injury or disability from workplace accidents and one providing pensions for invalidity or death not related to employment. Employees’ SOCSO contributions are matched by employers. The scheme is optional for those earning more than RM3,000 and for the self-employed.

- The government has since 2017 introduced a Self-Employment Social Security Scheme (SEEIS) for all taxi, e-hailing, and bus drivers who work full-time or part-time. In Budget 2020, the government expands the scope of SEEIS to other informal sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, own business and self-employed arts practitioners.

- Main issue: The relatively small amounts deducted for SOCSO makes it a bit forgettable – members of the public need to be reminded from time to time of their SOCSO entitlement. Though the amounts are relatively painless, a recent move to make SOCSO contributions mandatory for self-employed taxi and e-hailing drivers saw lukewarm response [paywall], showing the political difficulty of instituting contribution-based protection schemes.

Retrenchment Insurance

- Officially in effect from January 2019, the Employment Insurance Scheme administered by SOCSO is aimed at providing temporary and partial income replacement to workers who have been retrenched. Income replacement is capped at RM4,000 of wages.

- Employers and employees are required to contribute 0.2% of the employee’s monthly salary respectively into the scheme. The scheme also includes financial incentives in the form of allowances to encourage recipients to become re-employed and to take up reskilling training if needed.

- Main issue: There is some debate on whether Industrial Relations Act cases or recipients of severance packages should be excluded, but on the whole reception appears positive. The impact of this program to Malaysia’s data needs itself is valuable.

What Lies Ahead?

- EPF and SOCSO, with the support of other agencies and ministries, have been tasked with crafting a blueprint to improve the country’s social protection system. The magnitude and complexity of the task cannot be underestimated, and we expect this to be a continuous and evolving body of work. We look forward to the public consultation process.

Some questions from fans of policy and ordinary citizens:

What is an acceptable ‘basic’ standard of living? How do we determine that?

How should BSH amounts be determined? How should BSH be targeted?

Is a Universal Basic Income or Universal Basic Pension a feasible solution, given that many Malaysians will not have enough to retire?

Why have we not implemented a national health insurance scheme? What are the challenges?

Should we have specific subsidies for petrol, food etc. or just give households cash transfers?

Email us your views or suggestions at editorial@centre.my.

The Centre is a centrist think tank driven by research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas. We are a not-for-profit and a mostly remote working organisation.