Research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas.

Support job transition, facilitate career advancement

Rethinking Malaysia’s skills development approach

Pumping more investments on training programmes and facilities will not resolve accessibility barriers. We argue for a policy shift from purely supplying training to helping workers identify and realize opportunities that best fulfill their needs.

By Edwin Goh, Ooi Kok Hin & Nelleita Omar11 August 2022

The importance of a skilled workforce has been well established and every year, the government sets aside substantial investments to fund a range of training programmes and institutions, as covered in our primer. But this supply-driven approach needs to be complemented by an understanding of barriers faced by low-income workers and school leavers in accessing these opportunities. This editorial looks at Malaysia’s skills development policies and suggests the need for a new policy direction.

Current approach and policy gap

Traditionally, the government plays the role of training provider in the skills development system e.g. they build infrastructures and invest public funds to expand the range of course programmes and training institutions. There were 662 public training institutions in Malaysia recorded in December 2020, including 22 state-administered institutions.

In terms of programmes, the government’s initiatives range from targeted programmes like Place and Train for school leavers and the unemployed, and the Micro Connector Programme for B40 youths and women, to varying versions of ‘one-stop’ platforms, such as MDEC’s Digital Skills Training Directory, HRD Corp’s Upskill Malaysia, HRD Corp’s e-Latih, and, more recently, MOE-HRD Corp’s Microcredential Initiative.

Despite heavy investments on infrastructure and funds to accelerate skills development, the returns have been less than satisfactory. Accessibility remains an issue faced by those who want to reskill and upskill. Our 2020 survey on non-graduate delivery riders revealed that more than half of those interested in reskilling do not know where or how to access the training courses. Respondents also reported facing a lack of support to identify skills courses best suited to their needs and preferences. They would like to receive career advice and guidance, but there are few offerings on the ground.

Simply adding more programmes and institutions does not help workers to overcome access barriers. What they need are tools to support and facilitate their ability to plan their careers and navigate the skills development system.

From training provider to career facilitator

Making skills development accessible goes beyond providing training programmes. What we have found in our research, which is echoed by a report from Brookfield Institute, is that workers require support for job transitions. In contemporary society where jobs are becoming more precarious, rapid and frequent career transition can be expected to be increasingly common.

Is there a significant difference between a training provider and a career facilitator? We argue that they emphasize distinct policy goals: the former seeks to ensure adequate supply of training avenues and resources, while the latter focuses on helping workers to identify appropriate opportunities and provide the necessary support to assist them in realizing those opportunities.

As a career facilitator, the government can implement measures such as information organisation, course curation, simpler financial aid options, and career counseling and guidance. This shift in policy perspective helps workers overcome access barriers at two levels: firstly, by helping them to identify career or job transition opportunities relevant to their interests, needs and preferences. Secondly, by enhancing their chances to realize those opportunities via recommending appropriate reskilling or apprenticeship programs, together with supportive measures such as income replacement stipends.

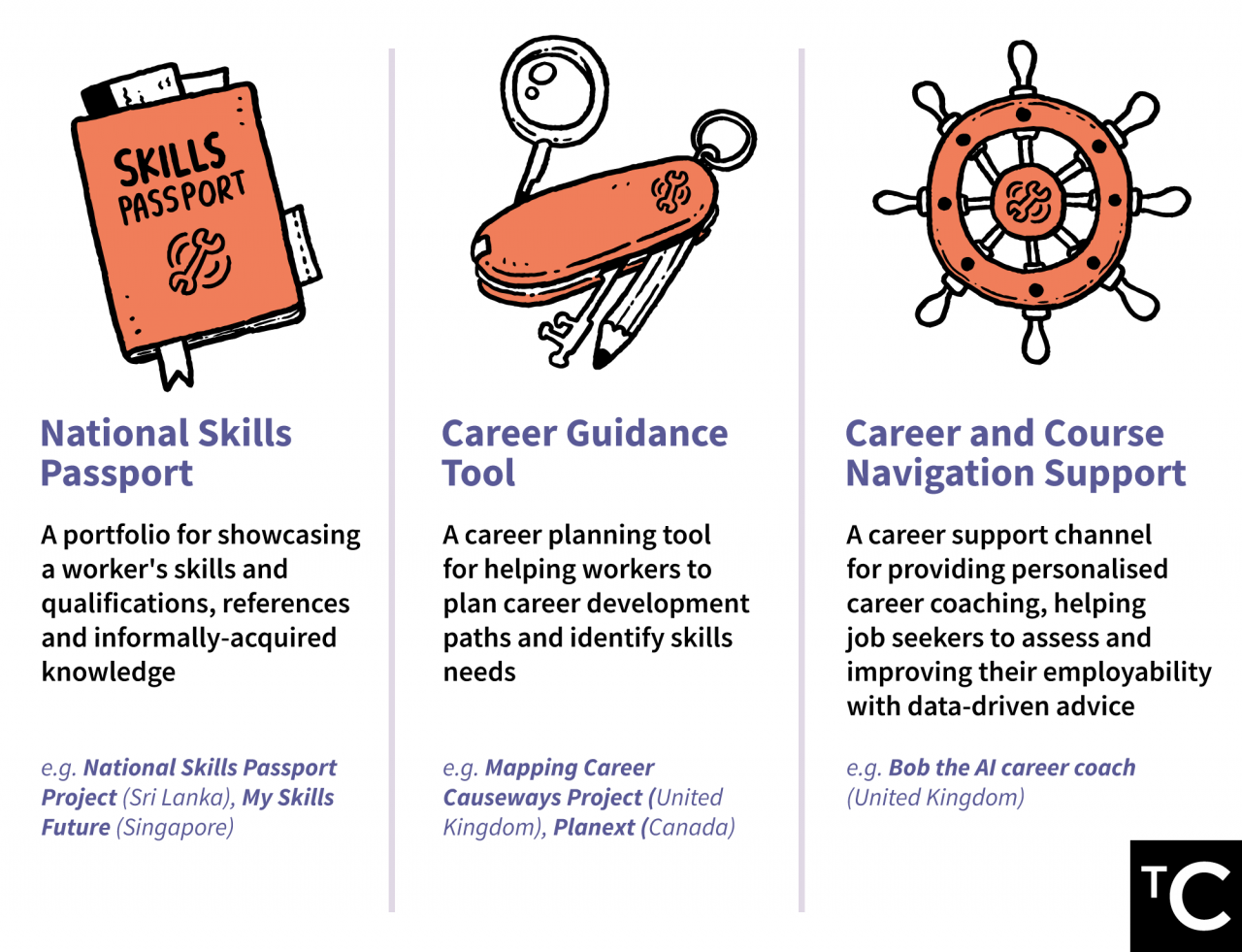

Countries such as Singapore, Canada, the United Kingdom, Sri Lanka, and the United States have implemented examples of such policy measures. The figure below describes a few policy interventions that could be game-changers for Malaysia’s workers, especially workers from lower-income bands (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Facilitative Skills Development Policy Interventions

Conclusion

Frequent and rapid job transition is expected to be more common in contemporary Malaysian society. Providing reskilling courses is only one aspect of skills development, and the government can help workers overcome accessibility barriers through policy innovations such as those outlined above.

At the time of writing, skill-related underemployment has become a looming labour market concern in Malaysia. The Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) reported that more than one-third of tertiary-educated employed persons work in semi-skilled and low-skilled jobs in the first quarter of 2022, as they lack the skills needed to fill the high-skilled positions. Many non-graduates, (and graduates too) have turned to informal gig work for livelihood, as the formal jobs available do not pay enough to make ends meet.

To ensure social mobility for all in this era, policymakers must go above and beyond to support everyone to access available reskilling opportunities, particularly those from less privileged backgrounds. We call on policymakers to begin addressing accessibility barriers by embracing the role of career facilitators for workers in need.

Email us your views or suggestions at editorial@centre.my

The Centre is a centrist think tank driven by research and advocacy of progressive and pragmatic policy ideas. We are a not-for-profit and a mostly remote working organisation.